PART ONE: A BACKGROUND OF LEADERSHIP AND RESPONSIBILITY

A Critical Overview

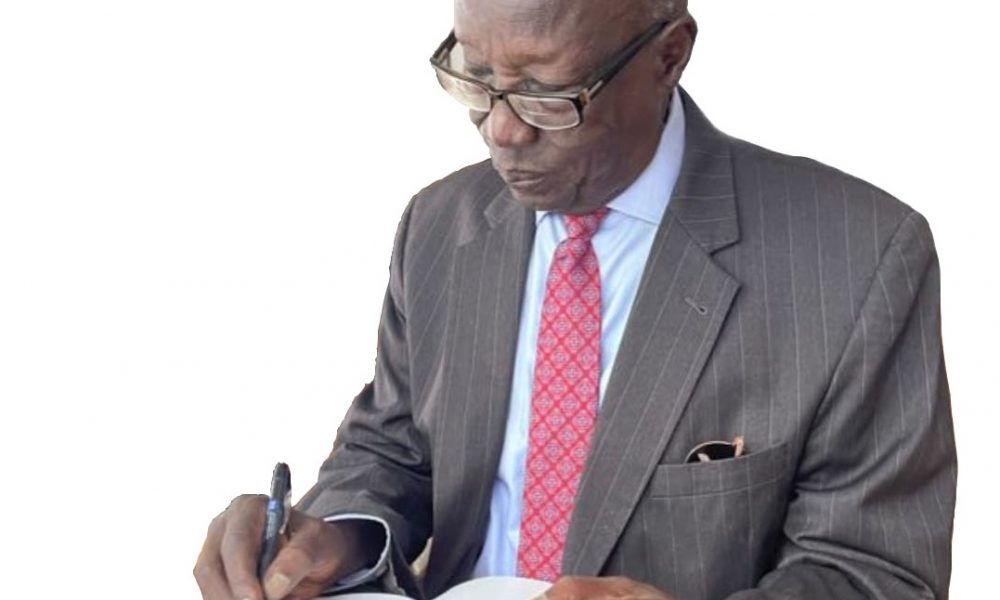

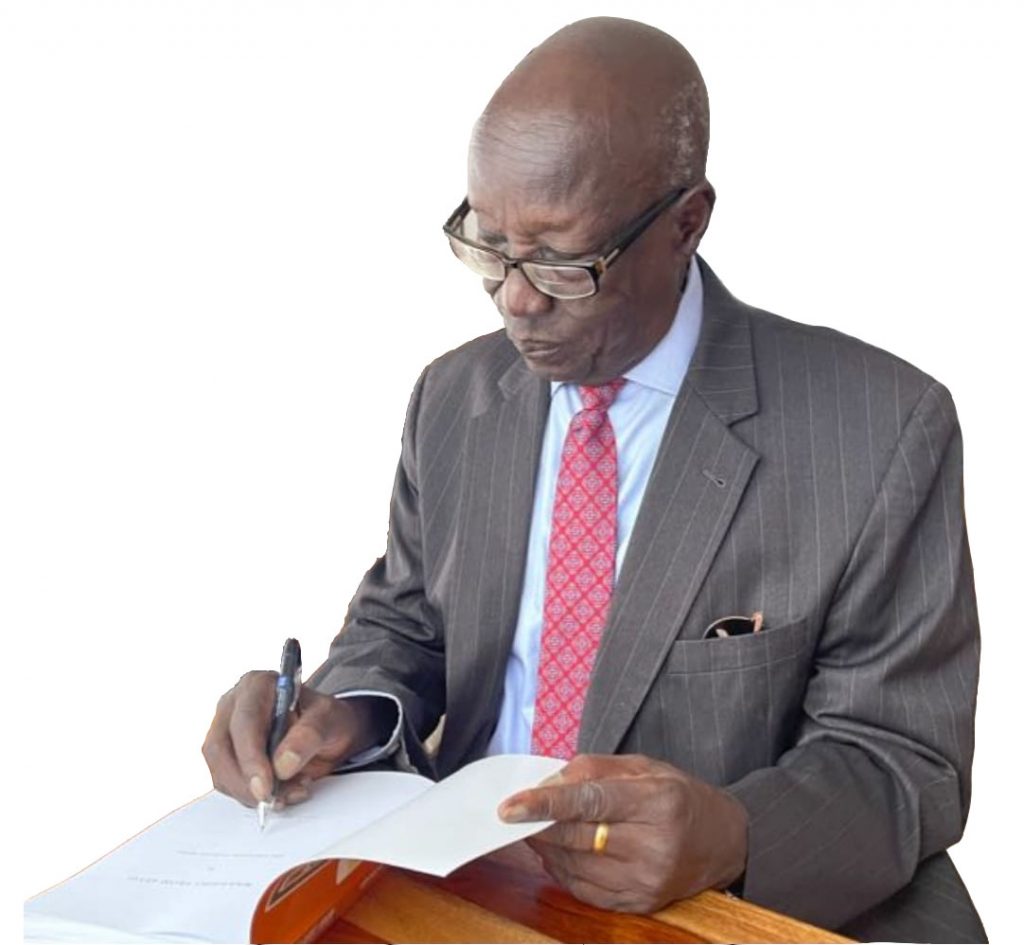

Mawien Deng:

Dr. Francis Mading, as you know, your proposal for an interim arrangement for security and stability in Abyei has generated intense debate among our people. The one-month workshop organized by Abyei Voice for Security and Stability in collaboration with Keep It Confidential adopted the proposal with revisions. And we hear that eight of the Nine Chiefdoms of the Ngok Dinka, with the Paramount Chief, have endorsed it. Even the Ninth Chiefdom that did not initially support it, was divided on the issue. Their Chief, supported by his immediate section, rejected it, but most of the members of his Chiefdom supported it. Even the Chief eventually moderated his opposition.

But the proposal has also been opposed by the Chief Administrator in Abyei and his leading comrades in the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement from Abyei. The official position of the Government of South Sudan is not known, but is being said in the media that you want Abyei to be an independent state or to be a UN Protectorate, which cannot be pleasing to South Sudan. All this has made your position very controversial. There are people, I believe the overwhelming majority of our people, who see the proposal as a continuation of your well-known concern for your people. And there are people, I believe a minority, but vocal, who see it as a continuation of your close connection to North Sudan, which they present as a continuation of the position of your father and your grandfather, who favored being in Northern Sudan.

But before we get into the details of the proposal and your family’s position on this controversial issue, can you tell us about yourself. Who is Francis Mading Deng and what motivated you to become so involved with the affairs of the tribe?

Francis Mading Deng

Thank you very much brother Mawien. Let me begin by saying that I am usually reluctant to speak about what I have done. It has an element of self-promotion, which I find distasteful. I feel put off when I hear people bragging about what they have done for the country. I prefer to operate discreetly behind the scene. And I have done so for decades for my people at the local level, for my country at the national level, for the continent of Africa, and for the international community on the mandates on internal displacement and genocide prevention. I have to say that I have been honored to have been given the opportunity for such a self-fulfilling public service.

What I have done has received national and global acknowledgement, but I have never been disconnected from the service of my people at the local level. And I now feel privileged to come back to my roots and be of service to my people. But you are right that my name is now in the public and has become very controversial. So, I appreciate the opportunity to shed some light on the situation and my position on the issues involved.

Let me state categorically that there is no controversy over the fact that we, the Ngok Dinka, are Southern Sudanese. The cause of South Sudan is our cause. Many of us have devoted our lives to the liberation of South Sudan, some through armed struggle, others through political action, and yet others through diplomatic engagement. I have documented this fact in numerous publications. The issue of Abyei has been part of this struggle. There can be no doubt about the support of South Sudan and its leaders for the cause of Abyei. That is why all my efforts in the promotion of the cause of Abyei have always been with the full knowledge and partnership with the leadership of South Sudan. We must also acknowledge that Abyei has been administered in the North, now Sudan, which has left complicating realities. The solution of the issue of Abyei final status therefore requires the cooperation of Sudan. That is why I have also consistently engaged the leaders of the Sudan and our Missiriya neighbors.

Although there is much talk about our being divided, a constructive view of our efforts will show that we are not only united by our shared goals, but that our means to those goals are essentially complementary. We all want the two countries of South Sudan and Sudan to recognize the overwhelming choice our people made in their 2013 reference to join South Sudan. We would also welcome the organization of another referendum in line with the proposal of the African Union High-Level Implementation Panel, AUHIP, chaired by former South African President Thabo Mbeki, which restricts the voting eligibility to the Nine Chiefdoms of the Ngok Dinka and other normal residents of the area, not the seasonal nomads. Since we are sure that any other referendum would have the same result, we share the view that an executive decision by the leaders of the two countries on the final status of Abyei would be a less time consuming and a more cost-effective way forward.

It is also our view that any of the three options can only be achieved and sustained through the cooperation of the two governments. If an agreement on the final status can soon be agreed upon to urgently bring peace and security to our people, that is the goal to which we all aspire. But if the process is likely to take any more length of time, then there is an urgent need for prompt more mutually acceptable measures to stop the killing and the suffering of our people, while talks on a final status continue. Because we believe that no solution can be imposed on a sovereign state, even by the AU and the UN, we have been developing a framework based on a win-win common ground that is more likely to gain the support of the parties and the international community. No self-respecting national leader can argue against an urgent need to ensure peace, security and stability for innocent beleaguered civilian populations, especially if they are claimed as citizens.

In light of this brief overview, the main difference there may be between us and our opponents is not on the goal of the freedom, security, stability and general welfare of our people, but rather on the most effective way of pursuing that goal. We believe that this can best be done through a negotiated agreement between Sudan and South Sudan. Given the closer bilateral ties now emerging between the two countries, we believe that the prospects for a negotiated agreement on Abyei, particularly the urgent need for peace, security and stability for the neighboring population, are much improved. Our opponents, on the other hand, believe that the solution will come from increased pressure on Sudan by the African Union and the Security Council.

The experience of many countries around the world, Palestine, Western Sahara, and Cyprus, to mention only a few cases, is replete with resolutions that are not implemented or even implementable. The Security Council has been calling on Sudan to withdraw its so-called oil police from Kec/Diffra to no avail. Dishonoring internationally guaranteed agreements with impunity has been the norm, not the exception, in the history of Sudan-South Sudan conflicts. No power is going to come marching in with troops to impose a solution on a sovereign state. Even if pressure were to succeed, it would be the result of persuading Sudan that it is in the mutual interest of both parties.

That said, whichever of our diverging approaches succeeds in bringing the urgently needed relief, peace, security and stability to our beleaguered area would be a most welcome and applaudable achievement. So, there is no reason for us to weaken ourselves with internal acrimony, instead of focusing our energies on ensuring the success of the strategy we have chosen to pursue.

The challenge to the legitimacy of my role

Mawien Deng

That is all fine, but the question some people ask is why you are playing this role as an individual when there are government institutions and authorized officials whose responsibility it is to take care of these matters?

Francis Mading Deng

I am glad you have raised this question. I am aware that voices have been raised about my legitimacy to speak for my people, since I am doing all this on my own initiative and not from an elected or appointed position. Let me answer this challenge by clarifying a principle that I believe applies to my brothers and sisters from the family of our late father, Paramount Chief Deng Majok, and our ancestral lineage more generally. Although our father was the Paramount Chief of the Ngok Dinka and we descend from a long ancestral line of leaders, I do not claim that we were born to rule or lead. But I say unapologetically that we were conditioned from childhood to be of serve to our people.

Many of our brothers, who became prominent in various positions of leadership, and sacrificed a great deal in the struggle for the freedom and dignity of our people, were not in the line of succession to chieftaincy. But they rose to the challenges and responsibilities of leadership in the service of their people with a sense of destiny that is connected to their background. And I am not saying that this is a monopoly of our lineage; it is part of the patrilineal culture we all share. We all want to honor the achievements and legacy of our forefathers and build on them with appropriate adaptation to the needs of changing times.

Let me elaborate with an anecdote that I believe will shed some light on the questions you raise. In 1983, I returned to Khartoum from my diplomatic post abroad to attend the meeting of the Central Committee of the ruling Sudan Socialist Union. The Ngok Dinka, and specifically our family, the sons of Deng Majok, were being accused of instigating hostilities that were threatening the security situation in Bahr-el-Ghazal and Southern Kordofan States. The Ngok Dinka community in Juba had organized themselves under the leadership of our brother, Dr. Zackariah Bol Deng, to advocate the cause of Abyei in Southern Sudan. And our brother, Michael Miokol, had started a local rebellion that was spreading into Bahr-el-Ghazal. The Governors of both Bahr-el-Ghazal and Southern Kordafan were saying that the rebellion was initiated and led by the sons of Deng Majok who were angered by the loss of power in the tribe.

Nineteen leaders and intellectuals from Abyei were detained in prisons and detention centers in Khartoum. Among them were Paramount Chief Kuol Adol Deng, Dr. Zackariah Bol Deng, a number of Chiefs, among them Achwil Bulabek and Patal Biliu, and intellectuals and political activists. Public statements were being made that they would be charged and tried for treason, a crime which is punishable by death. It was the time when South Sudan was acutely divided over Kokoro and prominent Dinka politicians were also under detention. In a meeting with Joseph Lagu, Vice President, he strongly advised me to keep out of the situation and to leave the country as soon as I could, as I might get implicated.

I understood what he was saying and appreciated his concern. But of course I could not turn my back on my people and remain in the government that was pursuing them. I was the only person from Abyei in the Central Committee meeting. As we were being attacked, I wrote a note to General Omer Mohamed El-Tayeb, the First Vice President and Chief of National Security, who was chairing the meeting, asking his advice on whether I should not respond. He wrote back advising me not to respond, but asked me to go to his office after the meeting to discuss the situation.

I went to Omer Mohamed El-Tayeb and we discussed the overall security situation in Abyei and South Sudan. I offered to intercede on both issues to try to mediate a solution with the parties concerned. I had an idea about what I would do on Abyei, since I had already persuaded President Nimeiri to adopt a policy on Abyei area to autonomously administer itself under the Presidency. That policy had been undermined by Kordofan, but could be reactivated as a potential basis for a resolution of the conflict. Since I knew most of the leaders in conflict in South Sudan, I also felt confident that I could negotiate a common ground. I was keen that I not be seen as only interested in resolving the issue of Abyei without concern over the situation in the South. I suggested that General Mohamed El-Baghir, former First Vice President, who was well respected by South Sudanese, could chair the South Sudanese mediation initiative.

Mawien. Deng

This is an important point because most Southerners do not know how much you have been engaged in promoting the cause of Southern Sudan. But will talk more about that later. Please continue your story.

Francis Mading Deng.

The First Vice President accepted my offer, but said he would have to get clearance from the President. It took a long time before Omer Mohamed El-Tayeb got clearance from the President. He showed me with excitement the handwritten approval of the President expressing confidence in me and authorizing full support for my efforts. I immediately embarked on my initiative on Abyei. On the South Sudanese initiative, General El-Baghir did not believe that the President s was sincere in wanting to resolve the differences among Southerners. He was convinced that the President wanted the South divided and to undo the Addis Ababa Agreement. Although I discussed my initiative on the South with the key leaders, Abel Alier, Joseph Lagu and Bona Malual, among others, and they all welcomed it, General El-Baghir remained suspicious of Nimeiri’s real intentions and wanted the President’s approval in writing. But that was not forthcoming.

It took me about four months of intensive negotiations to ensure the release of the detainees. Every morning, the detainees would be brought to the headquarters of Security Agency for the talks and taken back to their detention centers in the evening. Meanwhile, public statements were being made about their impending trials for treason. When we eventually succeeded, their release was announced with elaborate celebrations that were widely covered by the media. It was as though it was a second Addis Ababa Agreement. The First Vice President, in a televised statement, called the former detainees ‘Our Ambassadors for Peace’.

Mawien Deng

Did you have the support of your people for what you were doing?

Francis Mading Deng

That is a very relevant question. There was indeed controversy over what I was doing. As the detainees were about to be released, I discussed the situation with our brother Pieng Deng, who was a student of engineering in the University of Khartoum, but who, unbeknownst to me, was about to rebel. He said he supported what I was doing as long as it did not compromise the fundamental cause of our people. But there were people from our community who were vehemently opposed to what I was doing. They argued that the detention of the leaders was part of the struggle, even if it meant their death.

Indeed, a joint Ngok Dinka-Missiriya delegation, operating in partnership with the Kordofan authorities to protest the release of the detainees whom they presumably expected to be severely punished, perhaps even by death. Omer Mohamed El-Tayeb was flabbergasted. This indicates how divided our people were and that some of our own people probably had inside knowledge about the persecution of their people

My main purpose in telling this anecdote is to spotlight the argument of some prominent South Sudanese that I had no authority to negotiate the release of the detainees since I had not been elected or mandated to speak on behalf of the people of Abyei. They invited Zachariah Bol and me to dinner. Toward the end of the dinner, one of our hosts surprised me by asking, “Who mandated you to negotiate on behalf of the Ngok Dinka Community?” he asked. “Is it because you are the son of the Chief?” He went on to argue that I did not hold any elected or appointed position that entitled me to take such initiatives on behalf of the people.

I could not believe what I was hearing. And Bol, whose release I had secured, was there, listening quietly. I was furious. If he had said that before the dinner, I would not have eaten his food. I told him that if he was one of those who needed to be elected into a paid position in order to serve his people, I was not such a person. And whether he wanted to attribute that to my being a son of a Chief was up to him. But I felt a sense of responsibility without being paid to deliver that service. He came and apologized to me the next day. But the point he so crudely made is probably more widely shared. People do not understand it when an individual who is concerned about the plight of his people takes the initiative without some personal interest or benefit involved. For me, that is an essential element of inherited responsibility. As we grew up, Father often told Bol and me that he looked to us for the future of our people.

Mawien Deng:

I am glad you have clarified that point because there are people who wonder why you are so devoted to the case of Abyei. Some wonder whether you are receiving some benefit from some hidden hands to take the positions you have taken. So, how has the principle you have just explained played out in your life? What roles did you play for South Sudan and your Ngok Dinka people in line with your father’s vision of your service for your people? For instance, we have heard that you had a hand in the Addis Ababa Agreement and that it was you who inserted Abyei into the 1972 Addis talks. Some people even assert that the position you are following on Abyei represents the direction your father willed in his deathbed. Can you tell us something about that?

Click the link to read PART TWO The Contributions of Dr. Francis Mading Deng to South Sudan and Abyei – One Citizen Daily

Click here to read PART THREE The Contributions of Dr. Francis Mading Deng to South Sudan and Abyei – One Citizen Daily

Click the link to read PART FOUR The Contributions of Dr. Francis Mading Deng to South Sudan and Abyei – One Citizen Daily