By Kei Emmanuel Duku

South Sudan’s alarming rate of deforestation is directly linked to the country’s economic hardships.

Residents grapple with poverty, unemployment, and delayed government salaries, forcing many to turn to illegal timber logging and charcoal burning to survive.

The lack of alternative livelihoods and government support has exacerbated the problem, leading to widespread logging; an activity that poses a significant threat to the county’s biodiversity and long-term economic stability.

Pascal Sueperino, a 37-year-old government soldier- now turned charcoal dealer, says he turned to charcoal trade due to inconsistent salary payments. Despite a recent salary increase, he says civil servants have gone for more than 10 months without pay and cannot afford essentials such as food, medicine, and water.

“Soldiers and civilians from various backgrounds are illegally involved in the charcoal and timber trade,” admits Sueperino, adding that “These forests are vital, but we have no other means of supporting our families. The government has neglected us, leaving us with no choice but to turn to these illegal activities.”

Meanwhile, Sadiko Atoroyo a timber dealer operating in the Western Equatoria State notes that starting a timber or logging business requires three rolls of chains for pulling the logs, 10 rolls of spirals, spare parts, money to pay laborers who operate the machines and additional operational budget.

Atoroyo adds that since 2019 he has been operating a timber business in Western Equatorial both for Export and imports.

He however, notes that he has been limited by capital, adding that most people who have enough money realize their profit in less than two months especially when the machines are brand new and efficient.

He notes that the major challenge affecting his business is limited investment capital and foreign nationals who exploit the nationals by employing them as laborers, provide them with food only, with little pay.

“If you have 2-3 brand new machines, initial capital for paying machine operators and hiring of cranes and tipper lorries to transport the logs to the store, one can make good business. A lorry of logs costs between 80,000-100,000 South Sudan pounds,” says Atoroyo.

He adds that the flourishing charcoal, timber, and logs business has given rise to the establishment of shops dealing in logging machines and associated spare parts.

He identifies a shop in Juba along Jebel-Yei Road dealing in Husqvarna 272 XP machines because it is cheap and its spare parts are readily available on the market compared to steel Machines.

However, when the 2013 and 2016 conflict broke out, it affected areas such as Ibba, Zhara, Tombura and other logging hot spots in the Western Equatoria State capital Yambio. Consequently, most business people had to relocate to Juba and others to Kampala-Uganda. Their operations turned mobile and they would even go to towns like Nimule or Magwi in Eastern Equatoria State.

According to Global Forest Watch, between 2002 and 2023, South Sudan lost 2,160 hectares of humid primary forest, which represents 1.6% of the country’s total tree cover loss.

Mundri West and East, Maridi, and Ibba Counties are some of the areas in the West Equatoria State that have experienced serious logging prompting the state authorities to issue a ban on the activity and timber business.

According to Atoyoro, when the government issued the ban, it was specifically directed towards foreign nationalities aimed at discouraging them from the trade.

However, the ban gives foreigners an avenue to partner with locals and obtain operation licenses from the State Ministry of Environment and Forest to carry out illegal logging.

“The provincial governor of Western Equatoria State temporarily prohibited trade due to the influx of foreign entities. A committee was established to scrutinize existing and new operation permits.

Nevertheless, the ban proved ineffective as foreign actors could bypass regulations by partnering with local citizens. These partnerships allowed foreigners to contribute machinery and utilize local operation licenses,” he explains.

He reveals that after the ban was issued, loggers and timber dealers were asked to register for 50,000 South Sudanese Pounds before becoming full members of the Timber Dealers and Logger’s Association and being granted full logging rights by the state authorities.

Thereafter it is the operation license that will grant loggers access to the forest with the supervision of the traditional leaders or area chiefs and by-passing security checkpoints along the way to Juba and beyond.

According to Atoyoro, the widely lumbered trees for export within the Equatoria region are the mahogany trees. Although they are expensive to cut and time-consuming he says it is the most profitable tree species because it is used for various products such as furniture making, it’s resistant to water damage and it is durable.

A 2012 World Wide Fund report highlighted the unsustainable harvesting of forest products in South Sudan. The high demand for white “softwood,” specifically White Nongo (Albizzia), for construction purposes in Juba is contributing to the depletion of the country’s indigenous forests, according to the report.

Another report published by C4ADS titled “Money Tree” notes that teaks, Mahogany, and other valuable indigenous tree species in South Sudan if not sustainably managed are most likely to become extinct.

Some of the natural forests whose indigenous trees are on the verge of extinction in the Greater Equatoria belt are found in Morobo, Kajo-Keji, and Kergulu in Yei. Other forests are in Loka West, Lainya County, Imotong Mountains and Magwi County.

In the Western Equatorial State, Atoyoro observes that despite extensive logging, certain species of trees in Maridi, Yambio, and other places are still intact.

The ban was issued by the state government because most of the foreign nationals already owned about 15-20 machines for cutting trees and bypassing the local authorities such as the traditional chiefs.

However, the law now establishes that before starting to cut the trees, one must inform the traditional chiefs of the areas and pay a specific amount.

“Western Equatoria’s forests have been inundated by foreign nationals. Despite this influx, locals continue to grapple with economic challenges. To mitigate this situation, a committee, in collaboration with local loggers and timber associations, has been established. This committee seeks to regulate the entry of foreigners into the timber trade by mandating permits and associated fees. Authorized operators must contribute a portion of their revenue to both paramount and area chiefs. The timber trade offers substantial profit potential, with some operators reporting significant earnings within a few months of operation,” says Atoyoro.

From distilling to charcoal business

Gisma John Abdul, a resident of Suk Zande in Gudele West, Juba County, Luri Payam, and a mother of four, has transformed her life from brewing and selling alcohol to becoming a successful charcoal dealer. Driven by the need to provide for her family’s daily needs, Gisma entered the charcoal trade in 2019.

Gisma operates a network of charcoal dealers and truck drivers, coordinating the entire process from the forest to the city on the phone.

She has found the charcoal trade to be a more profitable and sustainable venture compared to distilling alcohol.

She narrates that starting the business required an initial investment of USD 300 for machinery and labor. However, she soon discovered that hiring workers was not as profitable as hoped.

She decided to focus on the business herself, relying on a network of people in the forest to buy and load charcoal for her onto the trucks she would send.

“I noticed that people are drinking less alcohol due to the worsening economic situation. So, I switched from brewing alcohol to charcoal trade. Charcoal has a longer lifespan than alcohol, making it a more sustainable business,” she explains.

Like many other traders, Gisma doesn’t sell charcoal in bulk. She packs into small polythene bags and sells each at 2,000 to 3, 000 South Sudan pounds. “This means I can make a profit of 20,000 pounds per sack but if someone insists on wholesale, I charge him/her double,” she explains.

A sack of charcoal costs between SSP 25,000 and 30,000 (about 10-20 dollars).

While the charcoal trade can be lucrative, it also presents challenges. Gisma faces extortion along highway roadblocks, security threats from armed militia, high cost of transport, and poor road networks.

She has cultivated relationships with brokers and charcoal suppliers in the forest – with whom she often exchanges food items like local brew, beans, and maize flour for charcoal at a subsidized price.

The production of charcoal involves cutting and burning large piles of trees. While this practice can be harmful to the environment, Gisma acknowledges that it is a necessary means of livelihood for many unpaid civil servants and unemployed youth.

Gisma’s dream is to establish a charcoal business in Juba but envisages business-related hurdles like high taxes.

Civil Society Calls Unheeded

Edmund Yakani, Executive Director of Community Empowerment for Progress Organization (CEPO), a civil society in South Sudan has over time raised concerns over the exploitation of the country’s natural resources, including oil, gold, and forests in the ongoing conflicts.

Yakani accuses the country’s political elites and military officials of engaging in illegal logging to fuel violence and extend the suffering of ordinary citizens.

He also highlights the influx of foreign nationals seeking to exploit South Sudan’s natural resources, leading to conflicts over resource management and ownership.

“If South Sudan does not have proper systems in place, we are going to see a similar situation to what is happening in the Democratic Republic of Congo,” Yakani warns.

He emphasizes the need for the government to invest in renewable energy sources, strengthen its capacity to regulate the illegal trade of natural resources and recruit and train more forest rangers and wildlife police.

Yakani attributes the high rate of destruction of South Sudan’s natural resources to the decentralized system of governance at the local level, where traditional leaders have power over natural resource management.

He calls for collaboration between local communities and government agencies to reduce illegal logging and mining.

At a legislative level, civil society players like Yakin continue to call for the Committee on Natural Resources and Environment at the Transitional Legislative Assembly to issue directives against soldiers and other civil servants who have abandoned their duties to pursue illegal charcoal businesses.

Energy Deficiency Driving Citizens to Forests

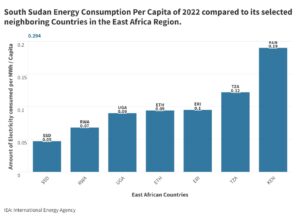

As of 2021, South Sudan had a total installed electricity generation capacity of only 120 megawatts, primarily from fossil fuels and solar power, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA).

Electrification rates in the country are among the lowest globally. Only 8% of the population had access to electricity in 2021, and those connected to the power grid often experience frequent blackouts or forced load shedding, and customers always complain of high tariffs. This has made standby generators a necessity for many, while charcoal and wood remain the most commonly available option for cooking.

In June 2023 South Sudan and Uganda signed an agreement to import electricity from Uganda. The proposed transmission project would enable Uganda to supply electricity to Kaya and Nimule, two of South Sudan’s towns near the Uganda border, and would help address the serious lack of access to electricity in the remote and urban areas of South Sudan.

Is it Too Late to Act?

Joseph Africano Bartel, the Undersecretary of the National Ministry of Environment and Forestry, blames the local population, national army, and rebel forces for the widespread deforestation in the Greater Equatoria.

In his view, insecurity in areas controlled by armed groups and delayed reunification of rival forces have hindered the government’s ability to manage natural resources.

He emphasizes the need for government investment in alternative energy sources, such as hydropower, natural gas, solar, wind, and geothermal, to reduce the reliance on wood fuel.

“Until we have a substitute, people will continue to cut trees for firewood,” Bartel says.

South Sudan’s forests and woodlands cover approximately 29% of the country’s total land area (191,667 square kilometers. However, this valuable resource is under threat from illegal logging, land conversion, and other factors. It is also estimated that 2,776 square kilometers of forest cover are lost annually due to these activities.

Alinda Brenda, a Program Coordinator at Climate Smart Agriculture Youth Network (CSAYN)-South Sudan, says that the high rate of deforestation in the country has resulted in climate change.

She cites the January to April heat waves that led to school closures and the floods that ravaged Greater Upper Nile, Unity States, and Greater Bahr el Ghazal as some of the consequences of deforestation.

According to the Venerability Climate Index 2017, South Sudan was ranked among the top five most vulnerable countries to climate change after the Democratic Republic of Congo, Central African Republic, Haiti, and Liberia 95% of the population relies on climate-sensitive sectors such as agriculture, forestry, and fisheries for their livelihoods.

Batalia Oliver, Director General of the Directorate of Environmental Planning and Sustainability in the Ministry of Environment and Forestry in South Sudan attributes this to a lack of policies, legal frameworks, and financial resources to address climate change-related issues.

On the other hand, Alinda criticizes the government for wasting financial resources on tree-planting campaigns without taking stricter measures to combat illegal trade. She suggests that arresting loggers and charcoal dealers could be a more effective approach.

CSAYN, is now training women to make briquettes, which require less firewood, and is promoting kitchen gardening to reduce reliance on trees for fuel and food.

“The charcoal briquettes are made from organic waste and can burn for hours,” Alinda explains. “You can use them for cooking beans, and just 10 pieces can last for about a month. We are also encouraging people to use solar panels, which can save energy.”

She appeals to the government to pass the Women Enterprise Fund Bill to enable women to access loans and start businesses.

Restoration programs and urgent calls for the adoption of environmental policies

The First State of the Environment Outlook 2017 report on South Sudan highlights the alarming rate of deforestation driven by the demand for charcoal and timber. This unsustainable practice has significantly impacted biodiversity, contributing to habitat loss, illegal logging, and a decline in wildlife populations.

The report recommends harnessing South Sudan’s natural resources to create jobs and generate revenue for basic services. It also calls for the government to address land tenure issues, develop wildlife tourism strategies, meet its Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) targets, and link energy development plans to climate vulnerability.

Malual Atem Ganuun, a Researcher and Policy Analyst from the Institute of Social Policy Research-South Sudan says that government’s failure to implement restrictions on logging and other climate change policies has exacerbated deforestation.

Ganuun advocates for a community-based approach to protect natural resources. He suggests that engaging local communities and raising awareness about the dangers of deforestation will help preserve the environment.

“While policy intervention should be considered as a last resort, community engagement should be prioritized because the primary environmental threat stems from urban dwellers who exploit the forests. Therefore, we must address the need for alternative livelihoods through agriculture,” Ganuun elaborates.

Ganuun also criticizes the government for failing to prioritize electricity use in cities, contributing to the high demand for charcoal. He now wants authorities to accelerate efforts to achieve the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goal 7 on access to affordable and clean energy by 2030.

According to the World Bank’s collection of development indicators, in 2022, South Sudan was ranked as the least-electrified country in the world, with only 8.4 per cent of its population having access to electricity compared to the 1% population having access to electricity from the main grid in 2013. Even those with access face challenges such as high tariffs, frequent power outages, and load shedding.

An additional report by Power Africa states that the country’s underdeveloped energy infrastructure and poor distribution networks contribute to this problem.8

“Access to clean energy and electricity should be seen as a savior and a rescue mission to our environment. We are already experiencing the dangers of climate change through floods and heat waves. But we also need citizens with goodwill to support our government’s efforts to address these challenges,” Ganuun explains.

Morobo County in Central Equatoria State which suffered significant deforestation during the 2016 conflict, has launched reforestation initiatives. The county has planted several trees across key government institutions, focusing on species like jackfruits, avocados, guavas, Nema trees, and mangoes.

The County Commissioner, Charles Data Bullen says that this campaign involves different partners including civil society organizations like Women for Change.

He explains that armed conflicts, incursions by loggers from other countries, and collusion between militia and foreign nationals has hindered natural resource management in Morobo.

The absence of a forestry bill has contributed to the lack of regulation and oversight in the logging industry. The proliferation of charcoal markets in cities like Juba highlights the demand for forest products and the challenges in controlling illegal trade.

This story is made possible with the support of InfoNile.